No products in the cart.

August 13

Taxes in Japan Part 3: Residence Taxes & The Japanese Fiscal Year

0 comments

August 13

0 comments

In the previous sections, we covered the very basics of how taxation and insurance premiums work in Japan. By now, you should know your way around income tax, and the progressive tax system – all very invigorating stuff, right?

*... crickets....*

Anyway, we still have so much to cover. Our main point of focus in this section will be "jūmin-zei" 住民税, or residence tax, also referred to as "municipal inhabitants tax". It's not quite as complex as the topics covered in the previous post, but it's a form of tax... which means "simple" is all relative. As such, before we dive into the meat of the subject, we first have to understand the Japanese fiscal year. It's the main point of reference for residence taxes, unlike income tax which lives within the regular calendar year.

Confused already? Wonderful! Let's dive in.

First, what's the difference between the fiscal year and the calendar year? (For most of you this is probably finances 101, but the fiscal year in Japan may be slightly different than that of your home country).

A fiscal year is the 12 month period that governments, business, and organizations follow for financial reporting, accounting, budgeting, and general work flow. It’s also referred to as “a business year”, because it follows the organization or country's natural business cycles. For our purposes, it can be thought of as “a tax year”. Residence taxes and insurance premiums are calculated at the end of it, and most bills are marked by it.

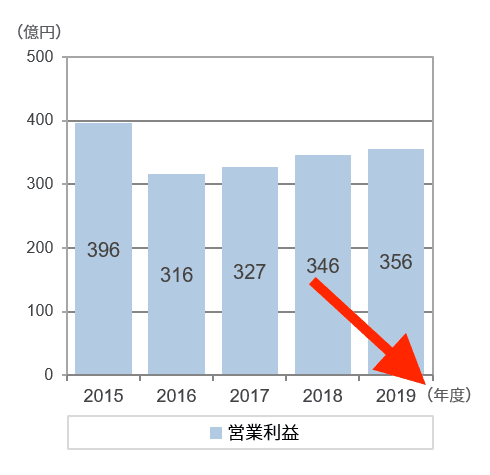

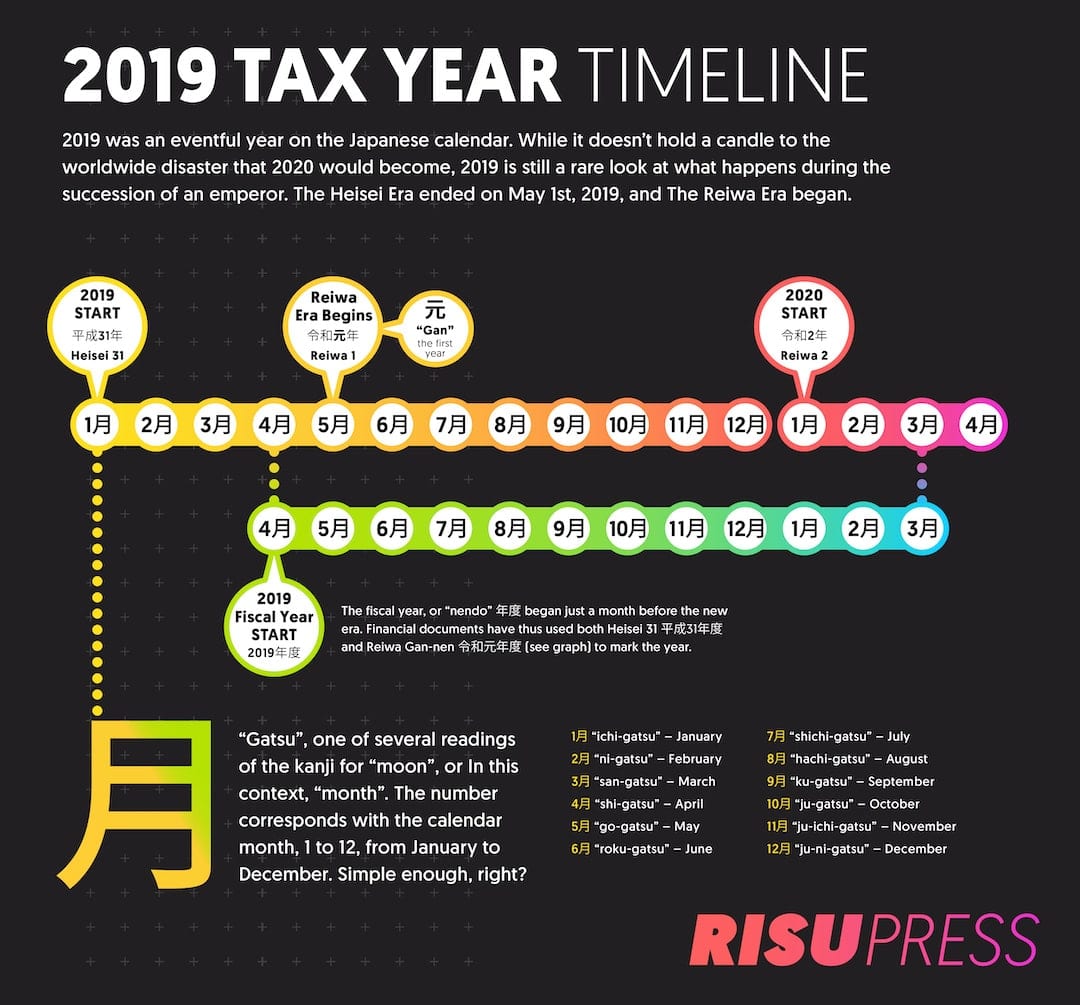

In theory, a fiscal year can fall within any 12 month period — even the standard calendar year between January 1st and December 31st. More often than not however, it’s offset from January by several months, varying by the country and organization. The fiscal year in Japan, referred to as “nendo” 年度, begins on April 1st of every year, and ends on March 31st of the following year. The 2019 nendo, for example, began on April 1st 2019, and ended on March 31st of 2020. Even though it ended in early 2020, it is still referred to as “2019 nendo”, or the fiscal year of 2019.

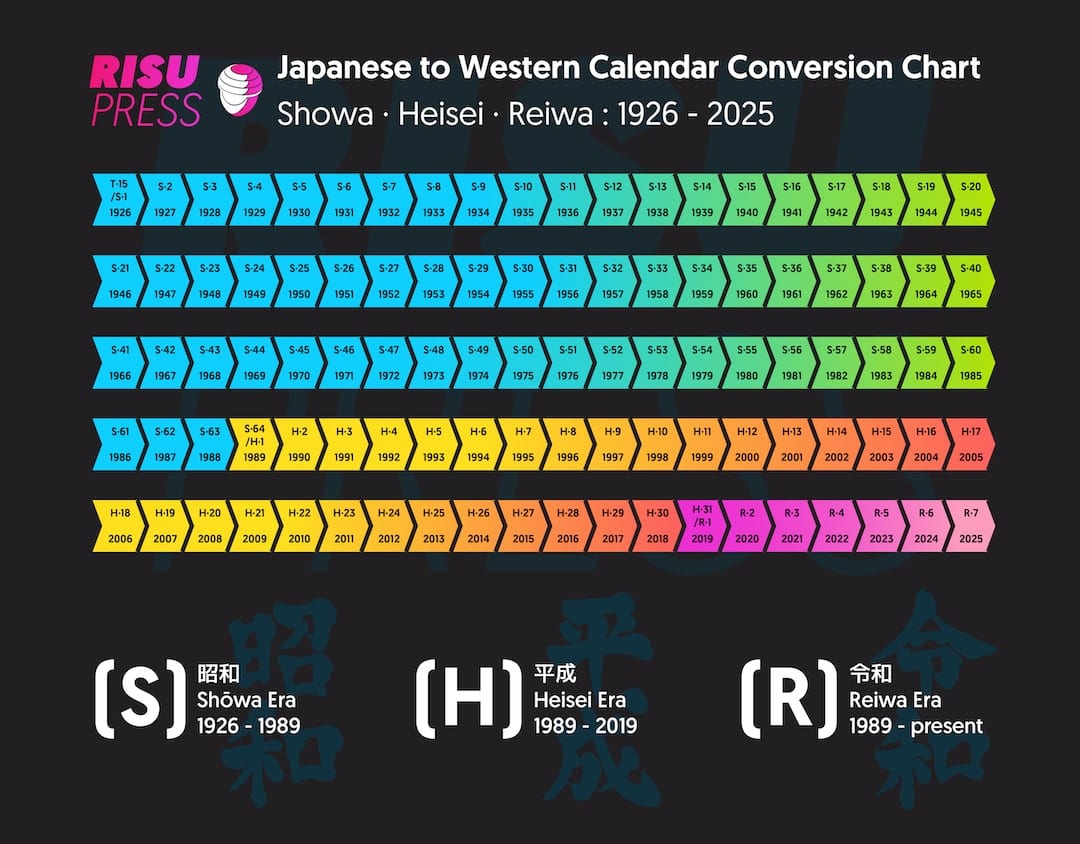

To make matters more confusing, most government agencies and official documents follow the Japanese calendar, rather than the Gregorian calendar (the one we use internationally, which is as of writing this up to the wonderful and easygoing year of 2020). The Japanese calendar follows the reign of each emperor, starting with the name of the era, followed by the numbered year of the emperor’s reign. Each time a successor takes over, the name of the calendar year changes, and the number resets to 1. For context, in 2019, the emperor was succeeded by his son, and the calendar year changed from the 31st year of the “Heisei Era” 平成 to the 1st year of the “Reiwa Era” 令和. With a new emperor comes a new name, and the counter resets.

It’s fairly straightforward as long as you’re familiar with the name of the current and most recent past eras. The three most recent eras are the Shōwa Era 昭和 (1926 - 1989), the Heisei Era 平成 (1989 - 2019), and the current Reiwa Era 令和 (2019 - present). The length of each era isn’t predetermined, but rather depends on the lifespan and ruling capacity of its corresponding emperor. The final reigning year of the Heisei emperor started in the beginning of 2019, and was marked as 平成31年, or Heisei Year 31.

Because, well… Japan, the passing of the baton on the Japanese calendar isn’t super intuitive. For starters, the first year on the calendar of every new era is not usually written as "ichi-nen" 1年, but rather as “gan-nen” 元年. For example, the new Reiwa Era began on the calendar as “Reiwa gan-nen” 令和元年, and that’s how it’s written on most official documents, including residence cards, bills, and of course, tax documents. “Gan” in this context is an obscure but important pronunciation of the kanji 元 which means “origin”, “beginning”, or “source”, and is usually pronounced as “moto” or “gen”.

With that said, you may occasionally encounter 令和1年 in the wild, but don’t be thrown by it — it’s the same thing… which would be fine if it weren’t for 平成31年 (heavy sigh). Things become a bit ambiguous when dealing with official documents concerning the year of an era change. In the case of Heisei changing to Reiwa on May 1st, 2019, both the 年 and the 年度 were retroactively categorized as 令和元年 instead of 平成31年.

In Japanese, the Gregorian calendar is referred to as “sei-reki” 西暦 which conveniently breaks down to “west-history”, or “the western historical calendar”. The Japanese calendar is referred to as “gengō” 元号, which translates academically to “era name”, but linguistically to “beginning - pseudonym” or “former time - number”. Brownie points for anyone who caught the 元 in 元号 using the “gen” pronunciation.

Most other tax guides skip over this very important piece of context regarding how taxes are calculated. Without it, orienting yourself within the tax cycle becomes counterintuitive and frustrating.

Residence tax, or “jū-min-zei” 住民税 in Japanese, is a yearly tax which all legal residents of Japan are required to pay once they have lived in the country for an entire year. It is paid to the municipality where the payer lived as of January 1st of each year. Along with health insurance, the rates paid in residence tax are based on the tax payer's previous year’s income, and are calculated after the payer files taxes at the end of the fiscal year.

Payment slips are sent out to every liable resident by June of each year, and provide two payment options. The payer can choose to pay in four more or less equal parts due in June, August, October, and January respectively, OR all in one lump sum. This is up to the payer, and either is acceptable as long as the payments are made on time. For some employees, residence tax may be taken out of their monthly salary, split up into equal parts from June when rates are calculated, to the following May.

The rate is a fixed 10% on the national level, and is calculated after all deductions are made from employment income. Unlike income tax which advances at a progressive rate, residence tax is charged across the board at a flat rate. This means that although higher income earners pay more money in residence tax than low income earners, everyone is still charged at a 10% tax rate. A person earning ¥2,000,000 a year pays 10% of ¥2,000,000; a person earning ¥20,000,000 a year pays 10% of ¥2,000,000.

Municipality — the locality where one lives, mainly broken down in the following ways:

Prefecture — the 47 prefectures in Japan which fall under four categories, represented by the acronym “to-do-fu-ken":

Residence tax consists of two different taxes that are combined to make a whole. These are the prefectural tax and the municipal tax. How the 10% is divided into these two parts is determined on the municipal level, and varies from municipality to municipality. In some instances it’s a 6% - 4% split, while in others it’s a 2% - 8% split. There are other potential combinations, but these are the most common seen in the wild, and regardless, all roads lead to a 10% rate charged to the previous year’s income after deductions. There is a common misconception among residents that one person will be charged more than another depending on where each person lives. While this is technically true on the municipal level, ultimately, every resident pays the sum total of 10%.

Pay your residence tax. If you don't, the negative consequences of your tax delinquency will permiate through every part of your residence status. Here are a few fun examples of potential consequences:

Inevitably upon failure to pay, your municipal office will seize and impound your assets. In Japanese this is called "sashi-osae" 差し押さえ, and it's really fun. In this procedure they obtain the legal right to forcefully:

This may seem like a no-brainer – you know, paying your taxes and all. But you'd be surprised how many foreign residents in Japan purposely or unknowingly ignore this, and invariably end up suffering the consequences. Yes, it's a pain, and a heavy bill to be slapped with. But the only thing worse than paying it is NOT paying it. Fortunately, with a dash of foresight, an awareness of how the tax system works, and some careful financial planning, you won't have to sweat this stuff. But, seriously... pay your residence taxes.

In the next part of this multi-part series where we'll look at everything we've discussed thus far on a more macro level.

Did you like this article? Please share it around!

Tags

Never miss a post – let us slide into your inbox with hot articles.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.